Gavyn Schlotterback played 58 baseball games at Paris Junior College in Texas last spring and another 44 over the summer for the Badlands Big Sticks in North Dakota without knowing that something was terribly wrong.

He felt fine. He played well. So well in Paris, in fact, that he was all-conference at two positions and all-region at a third and earned an opportunity to play baseball at Kansas as a catcher, alongside his brother Dylan, a third baseman.

Gavyn Schlotterback also had an enlarged ascending aorta. A portion of his aorta was so distended as to make the body’s most important artery, ideally about 2 centimeters in diameter, instead more than three times as wide.

“The way they explained it, it’s like a balloon,” Schlotterback said. “The more you inflate it, the thinner the wall becomes. So they said the wall of my aorta was incredibly thin, that it could have just burst it at any moment.”

Schlotterback’s routine physical upon arriving at KU alerted him to this dire cardiological issue.

He then proceeded to undergo open heart surgery in September and work his way back up from walking with great effort to serving as a full-fledged member of the baseball team in the span of just four months afterward — in time for the start of baseball season.

“It’s the best story on this campus,” head coach Dan Fitzgerald said. “Might be the best story in the country right now.”

When he first arrived in Lawrence just six months ago, Schlotterback had no idea that he could potentially have a heart problem.

“But as I’ve been told, it’s not something you feel until it’s too late,” he said. “You have 30 seconds left. And when they told me that, that was a little scary to hear, that you were one game away from no longer walking the earth.”

Playing for the Badlands Big Sticks, catcher Gavyn Schlotterback is pictured in the dugout at a game against the Willmar Stingers on Saturday, June 7, 2025, in Dickinson, N.D.

Fred and Anita Schlotterback were halfway back to Texas, having moved their two sons in at KU just two days earlier, when they got the call from Gavyn that he might need heart surgery.

He was just the second KU athlete ever to have something show up on an initial echocardiogram, according to baseball athletic trainer Jeff Roberts, since the department began including one as part of the physicals several years ago.

“Everybody else has been perfect,” Roberts said. “The number of individuals that have the issues is really, really, really small, but lord have mercy if we don’t do that. The consequences of that can be catastrophic on so many levels.

“Obviously for the individual, but in my mind, talking with Fitz multiple times too, it’s like, the ‘what ifs’ — that’s a heavy, heavy, heavy weight to think about.”

The Schlotterbacks promptly turned around and stayed in Lawrence for two weeks until it became clear, via a more in-depth echocardiogram at the University of Kansas Health System, that yes, their son would not be able to play baseball without medical intervention.

“Upon learning that everything they said was likely wrong was absolutely wrong, and that he needed to have an open heart surgical procedure in order to really save his life, there was a moment of emotion (for Gavyn),” Roberts said. “Fleeting, probably 10, 12 minutes. And he was like, ‘OK, let’s go.’ And that was his approach and his attitude to everything. He never balked.”

Schlotterback acknowledged that “it was heavy to hear those words come out of the cardiologist’s mouth,” and particularly frustrating given that he had indeed just played 102 baseball games (to say nothing of all his other time spent on the field) within the calendar year without incident. Suddenly he was being told he might not be able to play the sport again at all.

And he had to sit around and watch others do so for a month before he could get operated on in mid-September.

“The month leading up to that felt like the longest month ever,” Schlotterback recalled. “Just had to sit out from everything and watch the entire team do baseball. And I’m just on the side feeling like a normal person, because if you’re injured, you at least know you’re injured, know you can’t do anything. For me, it was just itching to get out there because I knew I could physically do everything they were doing.”

Except, through some significant misfortune, he simply couldn’t.

His parents had gone home — he has another brother, Ethan, who is still in high school. Fred, an engineer, and Anita, a pharmacist, were far more anxious about the surgery than he was, he said.

“I didn’t really think too much about it, just because I was in the mindset of ‘I have to get this done to play baseball,’ so I didn’t feel any certain way about it, didn’t have any nerves or wasn’t really stressed about it,” Schlotterback said. “But if you look at my parents, they were completely the opposite. They were stressing hard.”

After a preliminary imaging procedure came the surgery, for which his parents rejoined him. They would then stay with him for the following month and a half.

When Schlotterback went under the knife, the plan for cardiothoracic surgeon Dr. Emmanuel Daon and his crew was to perform what is known as the Ross procedure. That would have required removing Schlotterback’s bicuspid aortic valve — about 99% of people are born with tricuspid valves, and bicuspid aortic valves, in which two of the three leaflets are fused, can cause heart problems — and replacing it with his pulmonary valve. Then they would give him a new pulmonary valve.

The surgery didn’t go according to plan. It went much better than expected.

“They thought (the aortic valve) was damaged,” Schlotterback recalled. “But when they went in there and they fixed my enlarged aorta, the valve fixed itself. So they didn’t have to do any of the valve replacements, which was incredible, because now that means I’m not going to have to get another surgery later on in life.”

Needless to say, he was relieved to hear that news upon waking up from anesthesia.

“Out of all the possibilities of surgery, there was a lot that would have restricted my ability to be able to play baseball or do anything normally again,” Schlotterback said. “But hearing that I got the best possible outcome was truly a relief.”

He spent four days in the hospital. Then it was time to embrace the tedious process of building his strength with the mentality of a high-level athlete.

Within five days of surgery, Fitzgerald said, Schlotterback was back on the field.

“I couldn’t stand just not being out here with the team or being away from baseball for that long,” Schlotterback said.

What he was doing on the field, specifically, was walking very slowly. He had not necessarily alerted his teammates, who had checked in on him throughout the process, that he was going to be there. The coaches came up and asked him how he was feeling.

“You know, you’re just freaked out as a coach,” Fitzgerald said, “like, OK, once we actually start practice, I’m thinking we need to put a screen in front of him, or send him home, or do something, because, you know, he’s showing his scar, and the surgery went amazing, and he was just chomping at the bit to get back and I’m like, ‘Gavyn, I don’t even know how to talk to you right now. Like, I’m just so thankful that you’re good.'”

There was a lot of walking in those early days, even though he could only make it about 100 feet before needing to sit down and rest for 30 minutes. But doing so around Hoglund Ballpark made it feel real that he could potentially return to the Jayhawks — even as early as a few days after he had been cut open and lost all his strength.

When he wasn’t at the ballpark he was walking around the neighborhood, more and more each time he attempted to do so.

“I could barely walk down the street the first day without wanting to go back to bed,” he said. “But the good thing was that every day, you could physically see the progress. Instead of being able to just walk down the street, I could do two streets or three blocks, and eventually I’d be like walking up to the school and back.”

Then came cardiac rehab, “like one of our grandparents might do,” as Roberts put it. Three sessions a week walking on a treadmill at LMH Health, trying to get his heart rate up and prepare his aorta for the possibility that he might someday soon be an athlete again.

“I’m going to go out on a limb and say that he was easily the youngest patient that the cardiac rehab here in Lawrence has probably ever had, at least secondary to open heart surgery,” Roberts said.

He was an outlier in many ways, which was a big reason why he believed he could get back to baseball sooner than anyone anticipated.

“Everybody had told me that there was a small chance I’d be able to play baseball at all this year,” Schlotterback said. “But heart surgeries and their recovery time, it’s all for older people … Most people are out of their peak athletic shape.”

It was only a month or two after the surgery before he started to feel like he “could just return and do anything,” after he had been told to expect six months or longer. But his bones still hadn’t healed.

Roberts, who called Schlotterback’s attitude throughout the whole process “unfathomable,” said he was the type of patient for whom “you have to tug on the reins a little bit as opposed to light a fire underneath them.”

“I was doing more than I was supposed to,” the catcher admitted. “I’m sure I’m not supposed to say this, but I was doing everything I could to get back sooner. I was trying to prove everybody wrong, because I mean, I’ve been told by so many people that ‘you’re probably just going to redshirt this year. You’re not going to do baseball.’ And I mean, as an athlete and a competitor, you always just want to prove people wrong, so I used that to kind of just fuel my desire to do everything I can to get back sooner.”

By the holiday break, Schlotterback was able to get clearance from his hospital and his cardiologist to do baseball activities on his own in advance of his return to campus — “to kind of start being normal, for lack of a better way of putting it, again,” Roberts said. The KU staff sent him home with a deluge of programs: a throwing program, a hitting program from assistant coach Tyler Hancock, an exercise rehab program from Roberts, a strength program from strength coach Luke Bradford.

“We had so many different layers to kind of just getting things back towards normal,” Roberts said.

It was an opportunity to turn Schlotterback loose and let him do everything he could to expedite his recovery. And a few days after he got back from winter break, following an in-person visit with the cardiologist, he was officially fully cleared.

“And I asked Jeff on multiple occasions,” Fitzgerald said, “like, OK, fully cleared to … ? Explain fully cleared.”

Fully cleared to play baseball and to do what he did in his very first scrimmage: record a base hit in his inaugural at-bat.

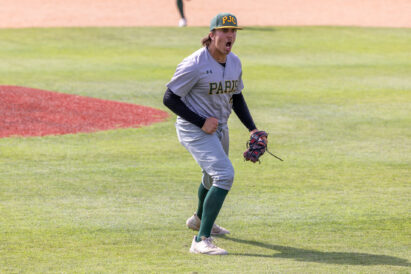

Paris Junior College’s Gavyn Schlotterback celebrates against Blinn on Thursday, May 8, 2025, in Brenham, Texas.

Of course Schlotterback was nervous. But from the moment he returned to action it was like he had never left, he said.

“To be able to be on the field for the first time,” Schlotterback said, “compared to just being in the dugout and watching the team live out your dream for six months, it felt great to just be out there and be with the team.”

His muscle mass and his speed aren’t all the way back, Fitzgerald said. But he still called Schlotterback one of the team’s top hitters, not to mention “the toughest kid I’ve ever coached, and it’s not even close.”

“I’m used to seeing an ACL patient, or here in the baseball world, a Tommy John surgery, and so much satisfaction and emotion associated with seeing that individual return to do what they do,” said Roberts, who in 2024 joined KU from Ohlone College. “That’s always immensely gratifying. This experience is otherworldly, beyond anything I could have comprehended before. I’m just beyond thrilled for him.”

And they’ve all had a bit of fun with the whole thing — which of course was only possible because of how smoothly it went.

Back when Schlotterback had only just returned to the field and was barely walking, a teammate of his was contemplating sitting out of practice after having fouled a ball off his foot the previous day.

“And he kind of came out and he’s like, ‘Yeah, I’m not sure I’m gonna be able to go,'” Fitzgerald recalled. “And I said, ‘Well, hey, listen, why don’t you go talk to Gavyn, you guys are both recovering from things, and just kind of see if maybe you can pick his brain on some ways to recover.’ And he’s like, ‘Coach, I think I’m good.'”

The more lighthearted invocations of his very serious ordeal aside, it’s been a sobering experience for Schlotterback, who said he still thinks about the numerous points at which things could have gone terribly wrong.

“Like I could not be here right now, and that’s just something, when you think about it, it’s surreal knowing that everything went right,” he said. “I mean, that’s just a blessing, to be able to be back out here and living my dream.”

According to Penn Medicine, more than 30,000 people die in the United States each year from thoracic aortic aneurysms — when a portion of the aorta swells in size — when they burst or tear, and hundred of thousands of Americans could have potentially undiagnosed enlargements like Schlotterback’s.

“Just knowing that we have those resources and that humans can find these things and fix them and you can return to being how you were, it’s incredible,” Schlotterback said.

In that first scrimmage after he returned to action, Schlotterback did indeed get a base hit the first time he stepped up to the plate. He also finished 2-for-3 with a double. Perhaps most impressively, on defense, he dove headfirst for one ball, and he blocked another with his chest.

Gavyn Schlotterback

Badlands Big Sticks

Badlands Big Sticks Paris Junior College

Paris Junior College Kansas Athletics

Kansas Athletics